Visible Copper. Strong Alteration. Only Metres to Go.

Copper veins and strong alteration at FMR’s Llahuin Project hint at a large copper system below, with drilling set to resume soon

FMR Resources (ASX: FMR) has pulled visible copper veins from its first deep hole at the Southern Porphyry target in Chile.

The drill has paused for now at 1,198 metres due to mechanical issues, but that’s not what’s caught our attention.

FMR was the first company we backed in 2025, and today it confirmed copper veins and rock types that typically form near large copper systems. In short, management is seeing the signs that often lead to major discoveries.

Replacement gear is already heading to site, and drilling should restart within the week, but what’s coming out of the ground more than makes up for a few days’ delay.

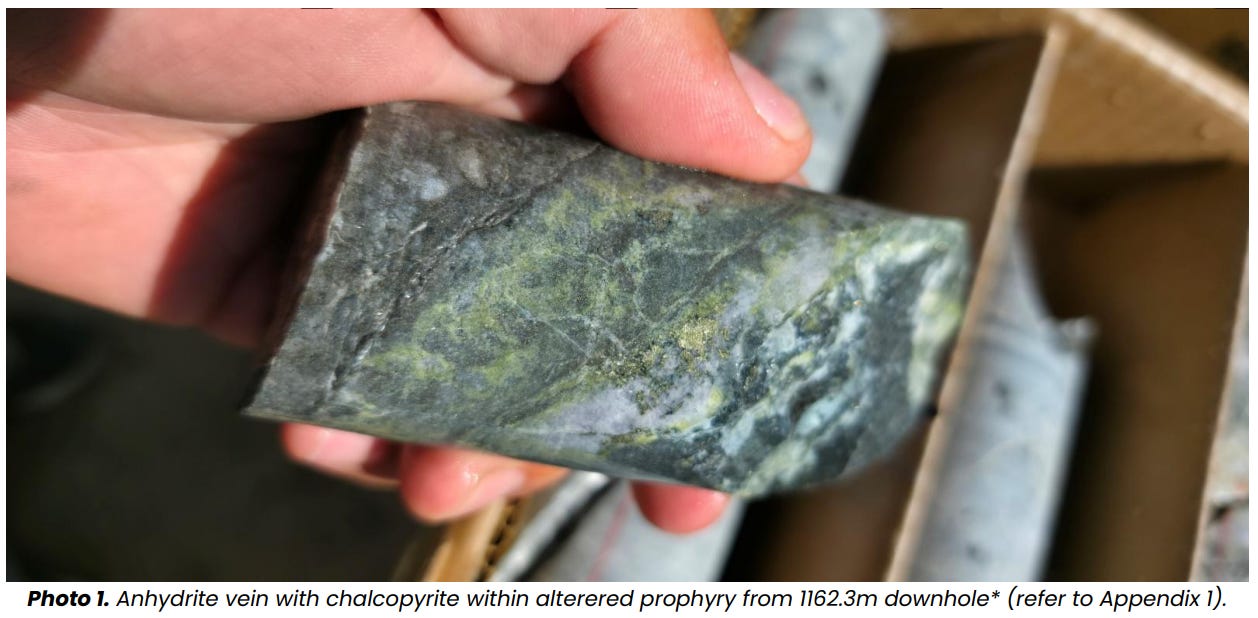

FMR is pulling up what you want to see above a porphyry system - copper veins running through altered rock.

At 33.5 cents and a $16 million market value, backed by $6 million in cash, we see this update as a strong step forward in the hunt for a major copper find.

Delays happen in exploration, and we’d rather see good rocks and a short pause than a smooth run with nothing in the core.

The short break gives the experienced team led by Oliver Kiddie, and backed by Mark Creasy, time to add to their growing data library and refine the next phase of exploration.

A Word From the Managing Director

Oliver Kiddie has been part of several world-class discoveries, and his take on the current drilling was notably upbeat:

“What we are seeing in the core continues to validate our geological and geophysical models. The copper veining, biotite alteration, and potassic overprint are exactly the features we expect above a porphyry centre. Importantly, ground conditions remain excellent.”

Some might focus on the pause, but the real story is what’s taking shape underground. They’re only metres above the main target, and the core’s starting to show the same traits their model predicted.

The Upper Halo: Copper Veins and Alteration

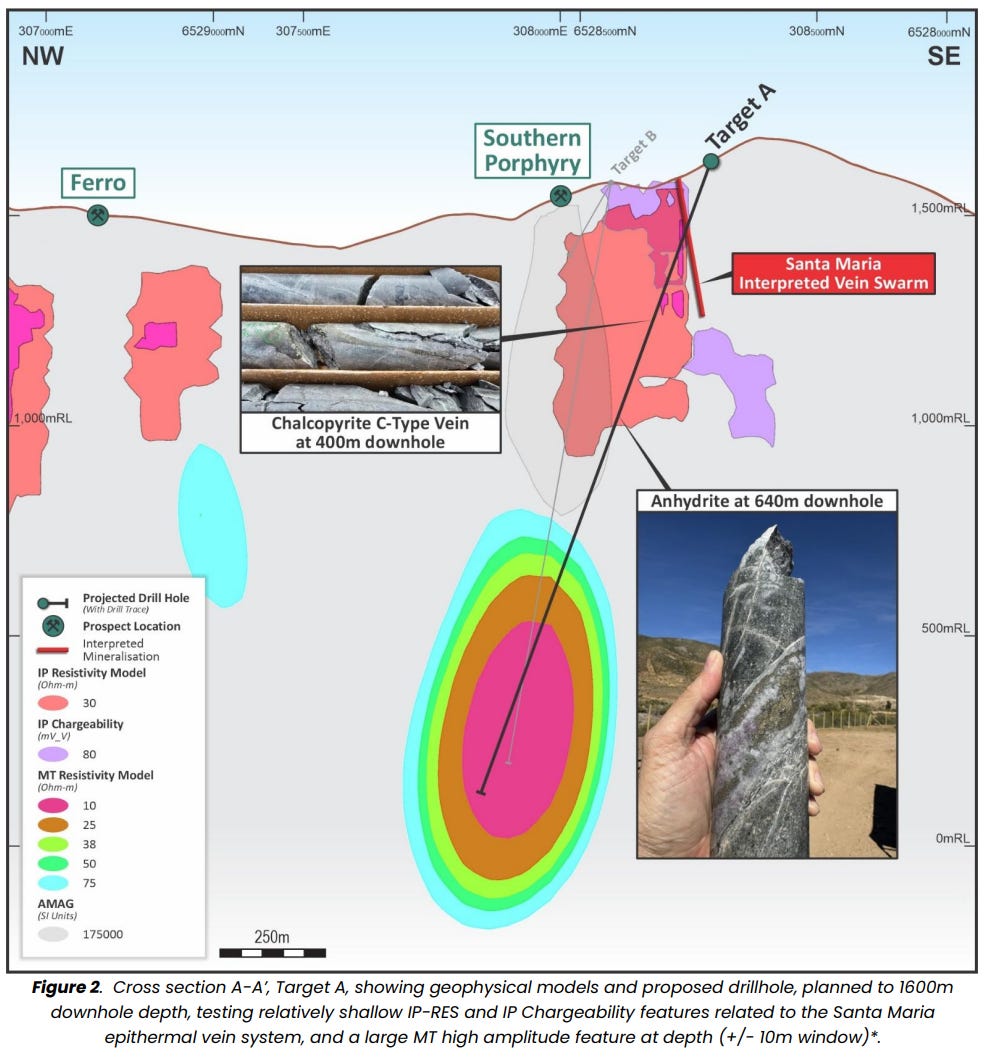

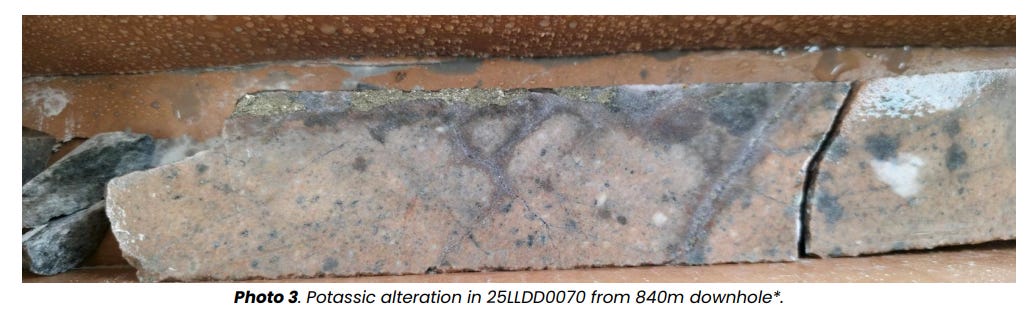

The drill’s now down nearly 1.2 kilometres, sitting in what geologists call the ‘upper alteration halo’. This is the zone that usually sits just above the main copper system, where mineral-rich fluids start to reshape the rock.

In this section, FMR’s logged copper-bearing veins and clear signs of heat and fluid movement from deep below. These are strong signs that copper is nearby and the drill is closing in on the source.

Put simply, when copper starts showing up in veins like this, it means you’re on the edge of something much larger.

They’ve also cut through a ‘crackle breccia’ around 1,160 metres - rock that’s fractured and re-sealed with quartz veins, a feature often seen near the heart of large copper systems.

These features are the tell-tale signs of an active and potentially significant copper system below.

Everything’s Lining Up: Geophysics and Geochemistry

Every metre FMR drills is checked against a detailed 3D model built from detailed geophysical surveys and historical data. So far, the rocks match the model perfectly.

The drill’s still sitting above the main target - a high-conductivity zone the model points to as the copper centre. And the signals are getting stronger.

From a technical view, this is textbook porphyry geology. Conductivity’s climbing as alteration intensifies, showing the rock’s responding just how it should near a copper system.

Handheld readings and early lab results are feeding straight back into the model, sharpening the picture with every metre.

Everything points to FMR moving closer to the main copper zone, and the company looks firmly on track.

Why Test The Rock? What Could It Mean?

FMR is testing rock from 485 to 1,160 metres to work out if the veins came from copper-rich fluids or just surface processes.

By checking elements like calcium and sulphur, geologists can tell if the veins belong to the same system that carried copper. If they do, it means the drill is already inside the outer edge of the mineralised zone and closing in on the core.

The tests will also reveal if these rocks are part of the same plumbing that brought up copper. If yes, the next few hundred metres will be pivotal.

The team’s also studying thin rock slices under a microscope, mapping how minerals formed to guide where to drill next.

Every test is about one question: are these rocks part of a major copper system?

The End Game Has Not Changed

Short-term sentiment might wobble when a drill pauses, but the story hasn’t. If anything, it’s looking stronger.

Copper-bearing veins, potassic alteration and strengthening geophysical data all point to a system with scale. FMR has done the groundwork and is now in the most critical phase, the final metres toward the main target.

The right minerals are showing, the science is lining up, and the rocks are behaving just as a porphyry system should before discovery.

It’s a waiting game now, but FMR’s inching closer to what could be Chile’s next major copper discovery.